The coast bush lupine is blooming in strange dancing spires that sway in the sea breeze, little lupine-witches, reaching for the salted sun. Their purple-pale petals, their soft smell of berries, their dip and sway in the wind, spell stories of the ocean-side to me, the beaches of West Marin in the springtime, when the lupines bloom and the spring wind picks up, foaming the waves, turning the sand to ghost-ribbons across the shore. Lupines and wind and osprey hunting and the warmer coastal waters of spring; these are all one poem, one story, one being, in my heart, in my experience of this landscape.

When the lupines are blooming, the osprey have returned and the sunny days are often full of wind, the water is warm enough to swim in. Warm is a relative term, of course-- warm meaning you can plunge without feeling as though you might have a heart attack from the shock. Warm meaning you stumble out of the foam feeling like you've been given a new skin made of ocean-breeze, lupine petals, the flight of osprey. And so it was this past week, at Limantour Beach with my brother, paying homage to osprey and lupine, wind and an ocean warm enough to shed a skin or two inside of.

I came out of the water feeling a great gratitude for this land, from which all of the thirteen

Gray Fox Epistles sprung, from which the

Leveret Letters continues to unfurl, from which my beloved novel-project with the beautiful

Rima Staines,

Tatterdemalion, was born. I had this sudden realization that these tales really

have grown from this ground here, from salt-tide, alder-wood, lupine scrubbrush, just the same as any sown seed. It occurred to me that maybe sometimes the best way to gather inspiration is to stop lunging about for new tidbits, new scraps, and to water the ground with thanks, with great awe and gratitude at the roots down below and all the tales they've made and fed. To unfurl pieces of those tales and hang them as if on a clothesline to bathe in the wind and sun; to take pages from those stories and lay them down for the nettle-roots to suck nutrients, for the osprey to fish up out of the waves, for the woodrats to secret away to their lodges and turn into bedding.

And so below I have included three excerpts from the three mentioned projects— the first from

Tatterdemalion (we are in the process of finding it a publishing home!), the second from the

Leveret Letters, and the third from

"Our Lady of Nettles," the twelfth Epistle, as flags of my gratitude to the wild places and animals and plants from which they were born, as markers along the Road of Story to inspire me as I carry on, mulching the land from which they came.

They were born from the jagged doorways in crab-shells, like the ragged-edged waxing moon, at once rough and delicate as embroidery.

They were born from the seal-people, the bugling elk and sledding children, the long-nosed court fools and blooming roses and racing sleek greyhound dogs that live inside the ever-shifting shapes of seafoam... and that place where the sole touches the cold salty water, and suddenly the foot becomes the bridge between the body and the story rising up from a scrap of foam to the heart, and then the beloved right-hand clutching its fountain pen.

* * *

Bells, Perches & Boots

(excerpt from

Tatterdemalion, a novel-in-progress collaboration with

Rima Staines)

No one knew where they had come from, how far or how long they had been walking, when they arrived at the edge of the ocean called the Pacific and unloaded their blue and gold cart in the center of a meadow-bluff of purple needlgrass and iris, just at the edge of a village. The one called Perches stuck his tongue out to taste the air, while the one called Boots sifted a handful of dirt and the one called Bells closed his eyes, plugged his nose, and listened. They reached their conclusion in unison—“it is good”— and got to building a fire. Boots hung a cast iron pot over the flames. In it cooked a quail and wild onion bulbs. Perches set loose the four tawny jersey cows who pulled the cart, and they began to graze.

The children of that village by the meadow-bluff of iris bulb and seed were the first to investigate. They came in pants of pigskin and nettle, here and there a special patch cut in the shape of a star, clamshell, wheel, from an old velvet or corduroy. They hung at the edges of the field, daring each other to creep one step closer, and one more, until a boy named Henrymoss had touched the blue and gold stripes on the cart, bringing back news to the others that it was real, sturdy and wooden, that it smelled like oiled leather and rust, with the faint sweetness of blackberries, that inside he had seen piles of bells, neat shelves full of boots, a bucket full of sticks, branches, wires, each with a leather tag and letters etched on it. That around the corner four cows were grazing, and their eyes were dark brown.

“We are connoisseurs,” a voice called out to the children where they huddled behind the cart, whispering. “We are pilgrims.” The voice had a lilt and a roughness that made several children, the younger ones, run off to the pine trees, to the huts where their mothers sat gossiping and spinning nettle fibers while sipping shots of dark mead.

Bells hung along the edge of the cart roof, and a pair of fine calf-skin boots was affixed to the front, above the door, like a figurehead. The boots were dyed red, laced with grommets, and embroidered with small crosses like stars. Ontop of the boots perched a kestrel, smaller than the shoes, cream and charcoal and pink-orange feathered, with the most beautiful, kohl-dark eyes the children had ever seen. She made a shrill call when she saw them.

Henrymoss, having been the one to touch the cart, felt he should maintain his reputation, particularly because the girl Jay, hair tousled and so black it seemed blue, was there with the others, watching and twisting her fingers in the tufts of her dark feathered hair. He wanted to run when he heard the kestrel but instead he walked around the cart, right to the fire where Bells, Perches and Boots sat stirring their quail stew and fiddling with a cowbell, a eucalyptus limb carved with crows, and a rubber rain boot, respectively.

“I thought pilgrims did it for religion,” Henrymoss managed through a dry mouth, after a moment’s staring at the blue tattoos all over the men’s hands, corresponding with their names; their beards like nests, their clothes which were simple robes like monks once wore, very rough-spun and sturdy, all mottled shades of brown and red.

Perches looked up at him solemnly. He had big brown eyes and a skinny, hawkish face.

“Oh yes, indeed. We have each chosen our worship, our path to perfection. You see.” He held out the carved eucalyptus stick. The crows etched into it were glossy, impossibly detailed. “This,” said Perches, “is where they are at ease, in a perfect balance with the wind, the light, the bark. They know exactly the branch. Is it not what all men and women seek?”

Boots stood then and slapped a broad hand on Henrymoss’s back, laughing. The boy jumped.

“This fellow is full of shit.” He winked. “It is my way that is holy. The Boot. How is it we tramp through the world? The Perfect Boot is the perfect union of foot, earth and path, weathering all mudslides, all asphalts, all heartbreaks. Come my boy, have a drink with us.” Boots was the biggest of the three, blonde and freckled, with a flushed, round face and nimble leatherworking fingers. Henrymoss noticed that he was barefoot, his soles and toes so callused and battered they looked like rocks. He sat down on a wooden folding stool next to the third man, Bells, who polished a coppery cow-bell in his lap, and poured Henrymoss a glass jar full of wine. Bells looked up at the boy, grinned, showing three missing teeth like black doorways, and rang the cowbell.

“Listen,” he said. “The bells toll in and out the ends of the world. Did you know that? Have you heard that they carried Bells, all those players, and their Lyoobov?” He ladled soup into a ceramic bowl and offered it to Henrymoss.

“Hey kids!” Bells yelled, whistling two tones through his three missing teeth. “Come out from behind the cart, come sit and have a bite and a tale.” Henrymoss took a big gulp of his wine, hoping it would make him look at ease and adult when they came. It was sour and strong in his mouth and made his temples pulse. The girl Jay was the first to pop her head around the side of the cart, hair making a spiked blue silhouette with the late sun behind it. She darted, taking leaps through the meadow. Two boys, Jeremiah and Samfir, followed her, and then slowly another girl, the small one called Mouse, though her real name was Mara, who could climb a tree faster than anyone, who always stuck her hands in holes in the ground first, just to prove she was tough, and did not deserve to be called Mouse. Still, her hair never grew longer than a thick fur, her ears were rounder than normal, and she was short; it stuck.

No one else followed. They’d crept back to the trees, to tell their brothers and their aunts—something new has happened, something strange. Throw dimes and old wires into the fire, leave out the wishbones for the old women with bobcat tails who live in the brush. Come see, come see!

And so the children Henrymoss, Jay, Jeremiah, Samfir and Mouse sat around the fire of those ramble-palmed tellers, those wheeling seekers of the True Path, all walking it together though their grails were myriad. A pipe full of strong tobacco was produced, and a set of fine china plates wrapped up in a child-sized quilt, tied with gut string. Perches fetched silver forks and knives from the inside of the cart, kept in a box lined with velvet full of slots and bands to keep the cutlery separate.

“Like corralling horses, ducks and pigs,” said Boots, handing each child a fine white napkin, a porcelain saucer-plate painted with fading bucolic scenes from a long distant rural past—neat brick farmhouses, maids in gowns, gentlemen on horseback—and a set of silver, buffed to a bright shine. Amidst the ragged simplicity of the three travellers, this supperware felt bewitched, molten in its fineness to the children. Like holding the stolen wares of a king from a story they thought was made up, but had turned out to be real, there amidst a rough whispering meadow, beside a blackened pot of stew and a cart all hung with bells and leathers and scratched by the talons of raptors.

* * *

These tales were born like the unfurling umbel of the stately and strange cow parsnip, that magnificent-stalked, human-sized flower of riparian corridor and scrub-hill. She always reminds me of the wiliest, kindest, wandering lady escaped from some mad-house, now running about with her white parasol stamped with the true love stories of the clouds.

* * *

The Leveret Letters, Chapter 9: The Cabinet of Wonders, excerpt

“The story goes that, after the Fall, at the beginning of the Camps, twins were born, conjoined at the hand. But the midwife, when told by the leader of the Camp to take the babies up and leave them for the coyotes, she couldn’t leave them alone. She stayed up the hill, under an oak tree, all night, praying. At dawn, a strange being emerged from the far edge of the oak forest. It was a Hill Saint. It was the spirit, you see, of that hill where the midwife sat. It looked like a very broad woman with a skirt of thick dirt and grass, with the big dark eyes of a vole. Her arms were twined with so many tiny rootlets they looked like they were covered in lace. She took the little twins in her arms and nursed them, not with milk, but with the sweet nectar that all hills have inside their veins.

“The next time another such child was born this side of the Bay, seven years had passed. The midwife of its Camp brought the baby up to the edge of Wild Folk terrain, as she was told. But she knew, from the stories passed between midwives, to call upon a Hill Saint, to raise that baby as its own. Instead of a Hill Saint, the twins conjoined at the hand emerged from the shadows at dusk and took the baby in their three hands, cradling.

“They were only seven years old, but it is said that those twins had become part Wild Folk, since they were nursed by such a one as a Hill Saint. They knew all the languages of all the animals and plants and stones, and all the Wild Folk who tended to their well-being. For a while, they took up residence here in the Inn, which was then very ramshackle, and healed sick animals. One by one, they raised little Strangelings. That’s what we like to say, instead of Poisoned Ones. The babies are Strangelings, and we, Holy Fools.

“Eventually, after a few of them grew old enough to take over the running of this creaking Inn, teenagers only, but that was old enough, and the twins had taught them about living, about tending bees and plants and birds, about playing, and never giving up on Joy, because nobody else in the world has that job, the twins built a green cart. They charmed a small herd of elk, and set off to rove, to roam. Sometimes, in those early days, they returned with books and linens and teacups from abandoned houses far, far North, miles beyond Point Reyes.

“That was four hundred years ago. Now, they are called the Greentwins, and while they look human, they are as immortal as Hills. They are mostly wild, a little bit angel.”

* * *

To all of the Holy Fools, and the ragged nettle who is their Queen, I give thanks. I give thanks to the ragged Nettle-Queen whose stinging language I've felt in my fingers so often as I gather and gather her leaves for my tea, the tea that sustains me as I write... the tea that thus is inside each word, the tea made from the body of that fierce and beloved weed so dear to my heart, Lady Nettle, friend of the Greentwins.

There's nothing like tromping through the hedge nettle with his rank scent filling the air from underfoot while gathering green nettles bare-handed to make one feel humble, feel overwhelmed with the sensory intensity of life—fingers buzzing, nose wide as an elk's, heart flung open. I imagine the hedge-nettle (

Stachys chamissonis) somehow like the vegetable version of the old edge-walking

jongleurs of the medieval troubadour era, the bards who played and juggled and sang for the common people, around campfires, not in court halls, the singers who had the hearts of coyotes. Something about the hedge nettle, always cooling his feet by the alder-creeks, smelling rank as a wild fox and sweet as lemon balm at once, puts me in mind of such wayfaring players who keep to the borderlines and the shadows, who are difficult to befriend but then suddenly, like the hedge nettle, you realize you love, for the feral rasp of that smell and all the memories and songs it holds—like Bells, Perches and Boots, like the Holy Fools and the little Strangelings. I imagine they line their shoes with hedge-nettle, they perfume their armpits and temples with it, to smell of animal and plant at once, rambling and fierce.

These green beings of the alderwood hold a deep dear place in my heart (as comes out in these story-scraps--so many nettles, so many alders!), both their physical medicines (what a triad-- red alder, stinging nettle, hedge nettle!) and the medicine that comes from being near them, the story-medicine of their lives.

* * *

Our Lady of Nettles, excerpt

Offer

For the first year you may not pick the nettles with your own hands. Every morning for a year, when the dew is still touching the nettle leaves in glinting speckles, you will brush your fingertips to the stalks in order to be stung like she was stung, in order to bring life and blood to your hands for the day’s work. The spines shine with dew, delicate as glass, and your fingertips will become strong. You will choose a patch of nettles to touch, to pray beside, to sit with daily. You will learn about more than nettles, this way. You may touch the tops of their leaves, and their seeds when they come pale-green and hanging in soft coils, but you may not pick. You may ask the nettles for the story of Nain, but only once you have given them your own story.

Every morning you will touch the nettle-needles with a fingertip, and you will leave white goose feathers at their ankles. You will bring water from the creek cupped in your hands. You will watch every new leaf begin and end at the patch of nettles where you sit, and every small bushtit who comes to eat the aphids from the stems, every red admiral butterfly who lays her eggs there. How, after all, can you cut and kill a thing, before you know who it is, before you do it the honor of your love?

You will walk the dirt path of offering every day. You will carry alderwood trays of nettle tea into the spinning room when it rains, tonics of nettle seed and the roots of dandelions for your sisters in the weaving room. When the Sisters of the Harvest cut the nettles in autumn, you will watch, and you will mimic how they offer handfuls of nettle seeds, a dab of comfrey oil to that open wound.

You will learn to leave the new pollen of hazel catkins in the fresh pawprints of bobcats, alder-catkin pollen in the pawprints of the two mountain lions whose territories cross here, when they come to drink from the creek where the nettles are retted, swinging the black tips of their enormous tails.

Leave the scarlet juice of the thimbleberries in the pawprints of the gray foxes. Leave shiny pieces of glass from the Bayshore at the entrances of woodrat nests. Leave handfuls of spiderweb on tree branches for the winter wrens to make their nests. Leave soaproot stalks wherever the deer have walked. In rain puddles, float the petals of the winter-blooming calendula flowers, from long ago gardens. Where the newts with orange bellies cross the paths from the hills down to the creek to mate after the winter storms, leave tiny red stream stones, one in the wake of each newt, so that the next walker might pause, and know the newts are out, shimmying each toward their own love, and step gingerly.

There is an ancient garden rose gone wild at the front door of the Convent of Our Lady of Nettles. It is as big as the whole wall, as big as an alder tree, branching and twining everywhere. The wall faces the southeast and the rose-light of the summer sunrise. At night, pick a rosebud and put it under your pillow. It is an offering for your own heart, to keep it open, despite everything, despite each day of your life before now which may have taught you that to close off the heart was the only way to survive. It is not easy to learn to soften, to touch each small creek stone and bare dirt where a skunk has nosed, with love, when it has been the safest thing to close, to hate, to use fear like a net around the body.

Ask the nettles, and they will tell you.

* * *

And so I carry on down the Road of Story, pausing to get on all fours, put my forehead to the dirt, and give thanks for where I've come from, and to where I am going, following sole and hand and heart, following the murmurings of the wily hedge-nettle, the irreverent dancing cow parsnip, the soft-skinned lupine-witches who poison the bodies of deer and rabbit and human but shoot the earth full of nitrogen-nourishment, walking the Road of Story to see where the next one will appear, quick as a bobcat darting down the path ahead, graceful as an osprey flying the shoreline. What a joy it is for a moment to dash as fast through the sand as the osprey flies, feeling like you are all wings too.

I think this feeling of gratitude rose up in me because I spent time this past week specially packaging up five

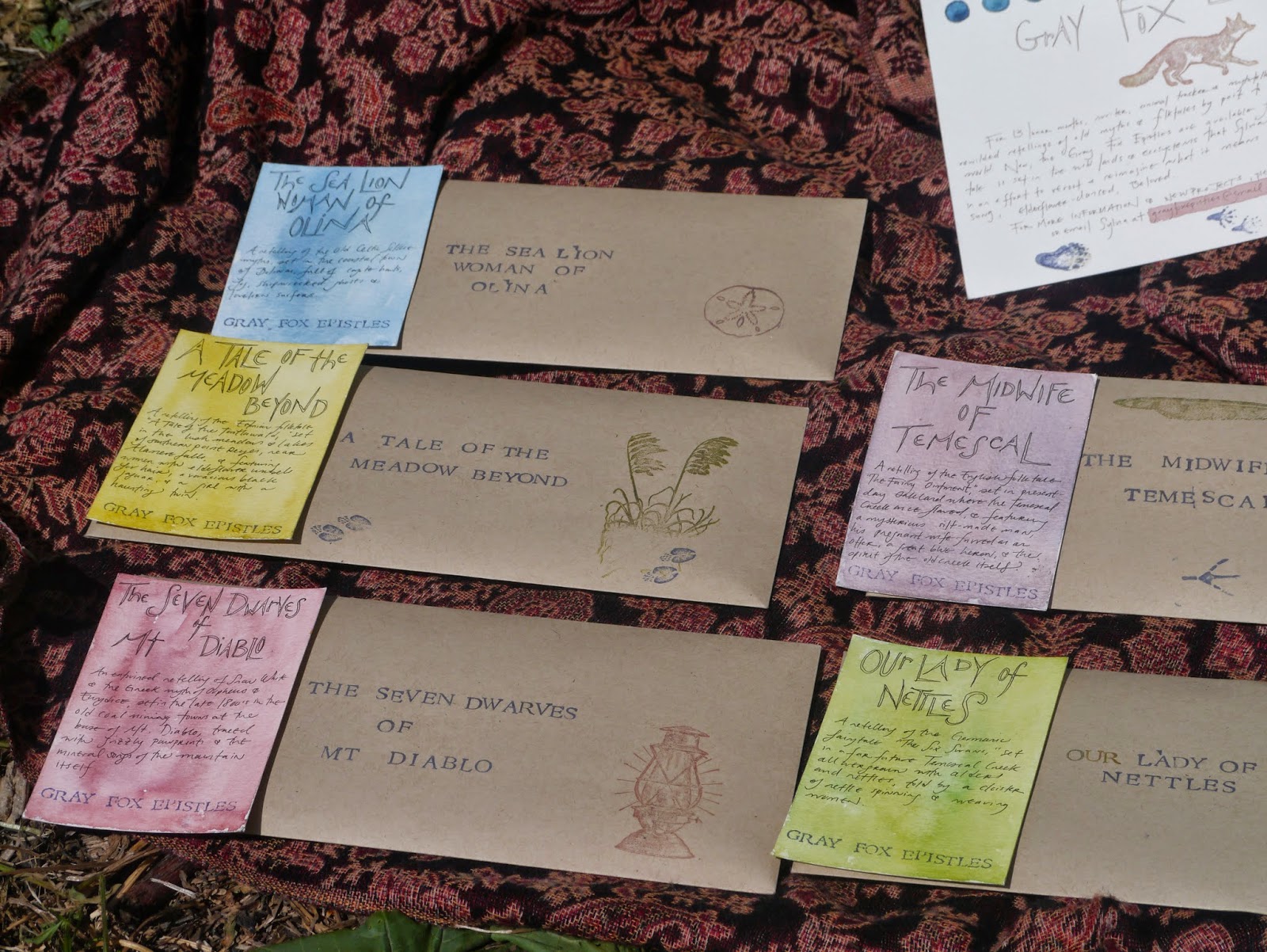

back issues of the Gray Fox Epistles to be sold in Molly of

Ambatalia's beautiful store in the old Mill Valley lumber yard.

I made a set of small cards, to be drawn like a tarot from a litte basket by customers, so that they might get a sense of the spirit and origin of each tale, and also a hint of the wild-ones who inspired them, from whose claws and umbels, talons and stinging leaves they were ferried and born.

I think pausing to create these cards, and then plunging into the salty ocean as an osprey wheeled overhead and the blooming lupine danced their witch-dances in the spring wind, hitched my heart open and knocked me sidelong with a kind of stunned gratitude for each and every wild encounter that has dusted pollen upon the story-embers in me and sparked them to light. Sometimes you stop, and look at a collection of things you've made, and shake your head, grinning, thinking-- where on earth did this come from in me? I can only say that I think it has something to do with the conviction of both Martin Shaw, David Abram, and many others I'm sure—that, in Shaw's words: "the psyche is far larger than the body. We dwell within the story, not the other way around. Telling the stories is a triadic engagement between the velocity of story, the intelligence of the tongue, and the imagination of whatever is listening in-- and something is always listening in." (xvi, from

Snowy Tower: Parzival and the Wet, Black Branch of Language). That something is the big old wild land (in Shaw's perspective); the psyche within which we and all our stories dwell is the psyche of the earth herself.

And so the great blue heron, the blue elderberry, the sea lion, grizzly bear and stinging nettle, somehow they are listening in, they are part of each of us— and isn't it a relief to imagine that perhaps the things we make don't need to come from inside of us in this intensely personal way, but rather are galloping through the landscape, looking for a hand to be written (or sung, or painted, or spoken) through?

This puts me in mind of the reflections of the poet Ruth Stone, as described by Elizabeth Gilbert in her

wonderful TED talk. Gilbert says that growing up in Virginia, "[Stone] would be out working in the fields, and she said she would feel and hear a poem coming at her from over the landscape. And she said it was like a thunderous train of air. And it would come barreling down at her over the landscape. And she felt it coming, because it would shake the earth under her feet. She knew that she had only one thing to do at that point, and that was to, in her words, 'run like hell.' And she would run like hell to the house and she would be getting chased by this poem, and the whole deal was that she had to get to a piece of paper and a pencil fast enough so that when it thundered through her, she could collect it and grab it on the page. And other times she wouldn’t be fast enough, so she’d be running and running and running, and she wouldn’t get to the house and the poem would barrel through her and she would miss it and she said it would continue on across the landscape, looking, as she put it 'for another poet.'"

I

love this image, that stories and poems are these great romping beasts migrating through the land

outside of us, not some divine "genius" within, as we are taught to think about creativity. What a relief!

These cards hold reflections of the beings who sang inspiration into my heart for each tale. I imagine them like pieces of an old tarot deck, pulled out of the dusty recesses of the cart of Bells, Perches and Boots, kept at the Holy Fool's Inn, read by the women in the Cloister of Our Lady of Nettles. And at once they are my lupine seeds of thanks, scattered across the edge of the sand dune to root and fill the ground with nitrogen again, fecund and fierce.