This autumn has felt every bit as abundant as the fall of acorns from the oak trees, and only this year have I finally learned to turn these sacred nuts to food; only this year have I come to realize in my body and not just my mind that acorns are food scattered all over the ground, given by the arms of the oak trees. They are more precious than any gold.

It has been a ridiculously long while since I wrote here, due to said abundance; I have felt a bit like the acorn woodpeckers who rush cackling between snags, stuffing all their careful holes with acorns, in a frenzy to make sure they get enough in before the squirrels and the deer and the woodrats do. The days grow shorter. I just looked out the window to find it fully dark and only just seven. The stars and moon hold us longer now than the sun. I feel things slowing. I feel the earth below saying--now, to the roots...

So, I feel I can catch my breath and share some of this harvest with you here... a harvest of the sweet moments and rambles that feed all of my words, and all of my spirit.

I learned to process acorns because, in a last minute sort of way, I ended up helping the wonderful Jolie Elan, of Go Wild, to put on her Oak Ceremony on Mt. Tamalpais, the sacred mountain I wandered so often as a girl. I sat in her backyard for many hours, cracking tanoak acorns, and eventually turning them to cake. I wrote about the whole process, and some of the lore of oak trees for her here (and painted a few acorns too).

We held the ceremony under big hearty tanoaks, the likes of which I have hardly seen. I am used to tanoaks that are small and scraggly, dying or already dead, covered in the black fungus known as Sudden Oak Death. Jolie decided to hold the Oak Ceremony for the tanoaks in particular. They were once the favored, and most sacred, of oak trees among the native people of this land. Their acorns are far and away the tastiest--the flavor is all butterscotch.(Perhaps this had something to do with the esteem in which they are held.) Now, as Jolie said, their kind is leaving this world, all but forgotten, alone, untended, unloved.

Unloved in the sense that, even if we admire and appreciate them, we do not gather their acorns any longer. We do not depend upon them for food, and thus we don't feel that more entwined, interdependent love for them that comes from necessity, from being humbled before our own hunger. We do not feel love for them as we would to a mother, and yet the oak trees are mothering in their abundance.

As Julia Parker, a wonderful California Indian basket-weaver and elder (and beautiful woman) says: “They told me when it comes, get out there and gather even if it’s one basketful so the acorn spirit will know you are happy for the acorn and next year the acorn will come.”

The Oak Ceremony was an attempt to remedy this neglect, to sit and sing and pray in conversation with the oaks, treating them as fellow beings.

We built altars to the land, expressing our reverence, our grief, our sense of loss and of wonder. We marched in a parade of singing through the trees. We held a Council of All Beings.

Some scientists believe that Sudden Oak Death has taken such voracious hold due to a lack of healthy wildfire and controlled burns on the land, as the native people used to practice. Others believe it is connected with a lack of phosphorus in the food chain, which was once provided by the abundant bodies of spawning salmon as they ran in silver ribbons up every creek, their bodies returning to the soil via the bellies of other animals--bear, hawk, raccoon. The web of things is so very delicate, and the trees teach us that when you pull one string, you really do find that the whole universe is attached.

Even if our sorrow and our singing and our acorn gathering do nothing in the face of the tanoak's possible extinction; even if no abundance of ceremony and story will save the life of this beautiful being, and so many others, it seems to me that we can never stop our singing, our praise, our expressions of grief and awe both; we have to keep talking to the trees, to the salmon, to the acorns, telling them that we appreciate their beauty and their lives. Because when we all stop doing this--well, I think then we shall be well and truly lost.

Sometimes, such sadness weighs on my heart very heavily. Sometimes there are so many things that fill me with grief, that make me weep, that I don't know how a heart can manage to hold the beauty and the great sadness of this world at once. Sometimes it seems to me that as a culture we have collectively turned away from our grief at the destruction of so much of this wild world because it hurts far too much. And it's true; it does. But inside of grief is love, and no matter how fraught our world can some days seem, no matter how frightening too... then there is the doe who comes suddenly wading through the marsh grass, stopping to watch you with black eyes and enormous velvet ears.

Then there is the sky, and the fog, and the marsh dotted with a dozen white egrets.

Really, I don't think I can articulate it as well as Mary Oliver can, so I shall let her do the talking:

“I tell you this

to break your heart,

by which I mean only

that it break open and never close again

to the rest of the world.”

Yes. Your heart must be broken open first, in order for the great old sacred world to come in, all bird-sung and root-thick and miraculous. In order for any of it to matter at all.

On the same afternoon walk with an old dear friend through the marsh at Limantour toward the strand, we saw first a doe, and then a stag, wading through the marshgrass. It is their courting time. Perhaps the stag was looking for her. They are vessels of pure longing at this time of year; they are so addled they are often hit by cars because they spend so much of their time wandering about in an erotic stupor. Seeing a stag surveying the marsh felt like a glimpse of the Green Man of old lore; the horned one of the woods, taking a last sweet roaming through his land before the fall into winter.

On the trail on our way back, we saw yet another doe with her adolescent child, who peered at us with great curiosity from amidst the brush. The mother did not seem very perturbed by our presence. She let me come very near, watching me. Our eyes locked for a long moment. I could hardly bear the beauty of her black eyes, her dark lashes. I felt entirely, calmly, reckoned by her gaze. It felt like some soft and hoofed benediction, or blessing, though I know it was just a doe, ascertaining whether I was going to leap after her child, perhaps distracting me from him.

Sometimes, the best thing is to be humbled before the eyes of another creature, before the dark mystery of them; we can be too quick to assume an animal crossing our path has some symbolism for our lives. The truth is, the world does not revolve around me (!)... The world is a web and the life of a doe and her almost-grown fawn is much more meaningful in its own right than it is symbolically, in relation to mine. The deepest gift from the eyes of a doe, touching mine, seems to me to be the gift of connection; that we are two beings sharing this world, and that of the two of us, her kind is far older and wiser than mine, and therefore above all things I should learn what I can about her life, her world, her ways.

That's what animal tracking has always been about for me. This is the oldest medicine: to kneel on the sand and learn the landscape of a bobcat track.

That it looks like it belongs to a female (if I were Tom Brown Jr. I would know for certain; as Sylvia Linsteadt I am not going to bet my life on it, but it feels like a solid educated guess); that she is in a direct register trot, which is a slightly quick gait for a bobcat. "Baseline" for a bobcat is a quick (overstep) walk; a trot means something pushed her slightly out of a comfortable dawn ramble—a sudden sound? Or maybe just the downhill slope?

Up the dunes and around the corner, the trails of brush rabbits were everywhere, and coyote too. These prints show a brush rabbit in a fast bound—out of baseline, hopping quick, perhaps between dunegrass cover.

Every track is a country and a doorway into the real lives of the animals on the land; every track brings me back into the great broken-open landscape of the heart.

|

| Serpentine (stone) outcrop on the top ridge |

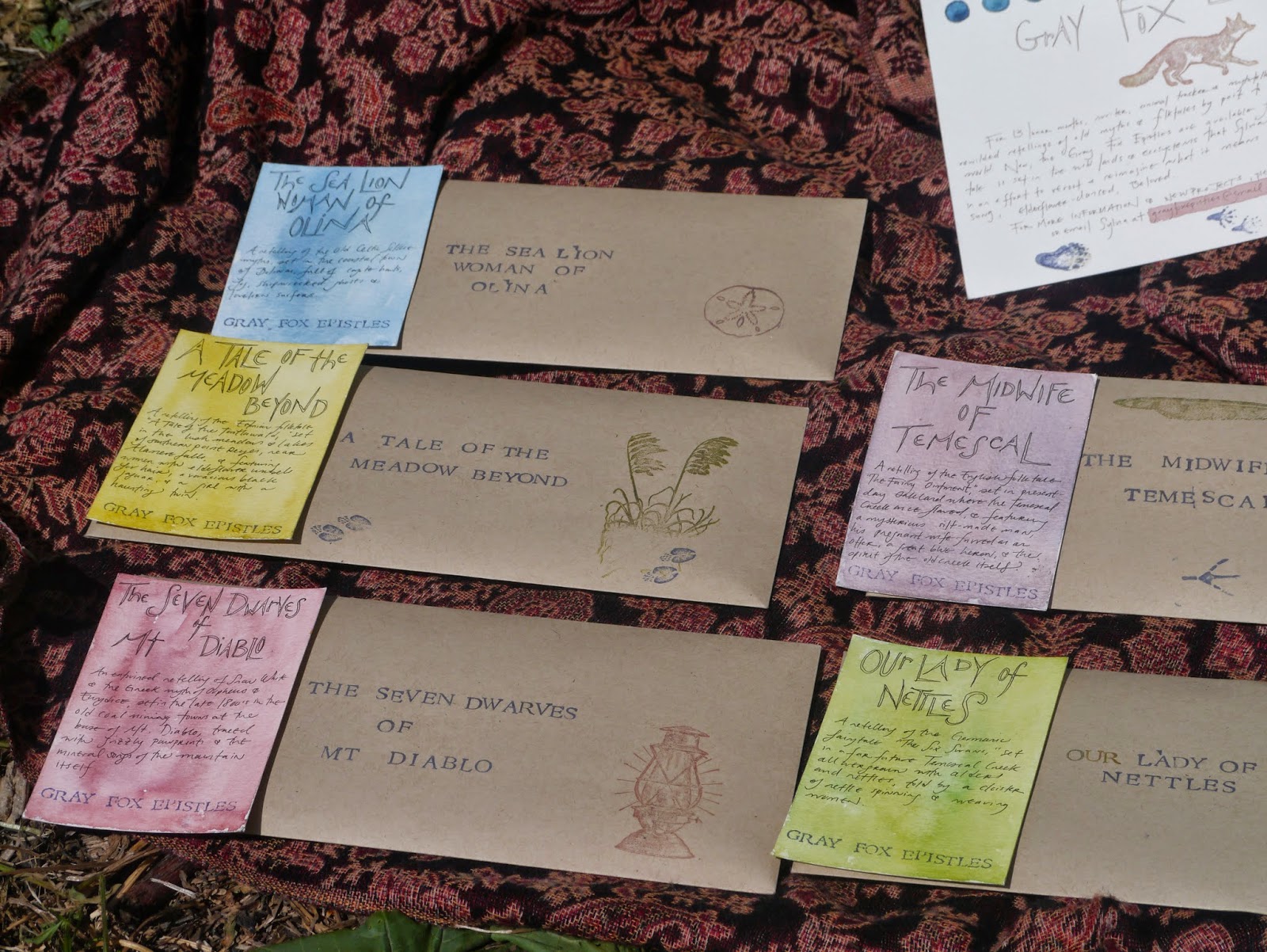

This autumn has had a certain serendipitous magic to it, all acorn-strewn and bobcat-pawed. Around the corner from my house, a magical little shop opened up for the months of September and October, and I met its two very extraordinary creatrixes, Catherine Sieck and Rachel Blodgett, through a dear old friend. I am astounded by the beauty of their work, the old earthen wisdom of it-- Rachel's plant-dyed, batik printed garments (including indigo moon underpants!), Catherine's exquisite shadow puppets and cut paper snakes and wreaths and hands. I was very honored to give a reading at their shop, called Serpentine, on the evening of October's full moon, along with a wonderful performance artist, Quenby Dolgushkin, who performed masked monologues of the feminine archetype.

It felt so good to share my own wild-pawed stories aloud and candle-lit. Sometimes it does feel as though the words enjoy ringing and winging out loud through the air, and off into the starry night...

|

| Serpentine, a metamorphic stone formed at ocean and tectonic plate boundaries |

Catherine and I have some magic up our sleeves... it involves cut paper and shadow puppets and tents and tales and tanoaks and who knows what else... for that you shall have to wait and see (and so shall I! Sometimes the harvest of new creations takes a while; though you can see the acorns up there in the branches, you must wait for them to fall!)

Meanwhile, mysterious small beings make immaculate tunnel-towers amidst the stones, all spiked with pine needles...

and the firs, growing tall amidst the manzanita, glow and sway in the glowing autumn light.

I spent this past weekend up in the hills of West Sonoma, carving buttons and bone and stone beads with a group of women. I processed nettle cordage for the first time, from a beautiful harvest of nettle stalks from the Sierras so tall I made about my own height in string from a single plant. To sit under the shade of oaks, twisting and twisting nettle fiber in my fingers; sanding manzanita buttons over and again, rubbing sheep fat on to shine them, with a group of women and the horses passing by at dawn in the mist, and the varied thrush singing for the first time I've heard this season; and a fire lit... this is peace.

But of all the gifts of autumn, fallen down from the trees, the one that has flung my heart open widest I found shivering beneath an oak during my time with that group of women, carving buttons and beads. I was about to dump the dregs of my tea onto the ground when something gave me pause. I looked down and saw a tiny silver creature hunched on a leaf, shivering and shaking. I crouched near, and found it to be a baby mouse. My dear readers, I have never seen anything so dear in my entire life. I could hardly bear it.

It was very clear that this wee one had been abandoned, or orphaned, and while I know that baby mice are a tasty treat for many a creature, this mouse lay in my path so pitiful and sweet, and my heart would not let me leave him to die slowly of cold, or starvation. Predation was unlikely until all of us had cleared out. So another woman and I scooped him up in some wool and moss and tucked him into an empty can. Immediately, he curled into a little ball, paws to nose, and stopped shivering. I nearly wept at the sight of the small pleasure he found in wool and curling nose-to-paws. I nearly wept, at the zest for life which all creatures have.

I couldn't reach WildCare that evening, so I took him home with me. He squeaked expectantly and robustly when I opened his box, and his little chirrups nearly undid me with their sweetness. I got up in the middle of the night like a fretful new mother to change the hot water bottle for a fresh one, so he stayed toasty warm. The next morning, I was beside myself with worry the whole drive across the Bay to the wildlife shelter. I didn't dare peek in his box, for fear the little one had died; after all, he had taken no water or nourishment in at least 18 hours, and was so small his eyes were still closed. But when I arrived, he was still breathing. I rushed him in, all shaken up and teary. The kind people behind the desk indulged me, though of course they see a thousand baby mice a year! They are very good at what they do, and they whisked him off to be cared for. They will re-release him into the wild when he is old enough. Even if it is only for a week, the little deer mouse will be able to enjoy the pleasures of what it means to be a wild deer mouse, bounding and burrowing in the grass and soil and eating all manner of nuts and seeds.

This little mouse did something to my heart. I stood there, outside Wildcare, for a good ten minutes, idly looking at the beautiful birds of prey they keep, birds that can no longer hunt or fly in the wild. Really, I was trying not to cry. Really, I was thinking of the tenderness for that single baby mouse which had seized me like a prayer; I was thinking of the love all mother animals have for their children, and the utter helplessness of a baby mouse without his mother, and all the tenderness there is in this world. Every creature is born into tenderness, though it may last only an hour. This baby mouse, he was a tiny silver miracle, and we were blessed to meet him for an evening, and see him on his autumn way.